Competition and Choice, Part D: The Doctor Cartel

Exploring the Common Ground Principles: Health Care

Exploring the Common Ground Principles: Health Care

Principle #3: A competitive and accountable health care system would help control costs by (i) ensuring that consumers pay a portion of the cost of medical services and products; (ii) allowing consumers to shop competitively for health insurance coverage or contract directly with health care providers for services, as they choose; and (iii) leaving room for health care providers, insurance companies, and the states to experiment with different methods for delivering services and reducing costs.

When we talk about reducing health care costs, there are some large institutional players that make easy targets. Giant pharmaceutical conglomerates, heartless insurance executives, and faceless hospital administrators all make useful scapegoats in op-eds and Congressional hearings. And indeed, they all bear some portion of the blame. But there’s another group of players quietly doing its part to keep prices high: doctors.

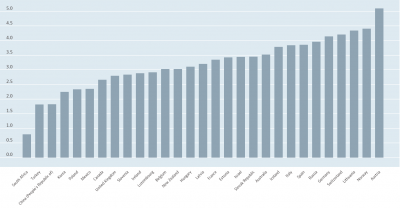

In an article for Slate, Matt Iglesias writes that doctors essentially operate as a cartel, limiting the number of new doctors and keeping prices high. American general practitioners are the highest paid in the world, and our specialists are out-earned only by those in the Netherlands (an American orthopedist earns, on average, $443,000 a year; a dermatologist earns $410,000). In fact, we have fewer doctors per capita that just about any industrialized nation, according to the OECD:

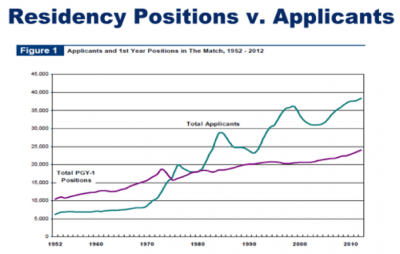

This chart has created some worry about a doctor shortage. But the tight market for physicians isn’t due to lack of interest. There are plenty of people who want to be doctors, and getting into medical school is harder than ever. It’s institutional design that’s keeping the number of doctors low. Consider the chart below, which shows the gap between graduating medical students and available residencies, which medical students refer to as “the jaws of death.”

This chart has created some worry about a doctor shortage. But the tight market for physicians isn’t due to lack of interest. There are plenty of people who want to be doctors, and getting into medical school is harder than ever. It’s institutional design that’s keeping the number of doctors low. Consider the chart below, which shows the gap between graduating medical students and available residencies, which medical students refer to as “the jaws of death.”

Iglesias offers one place in our health care system where doctors do not appear to be mailing outsized invoices: Medicare. The federal government, as an enormous purchaser of services, has managed to bargain prices down to a more reasonable level than most insurance companies have. And while we often assume that doctors would not accept these lower rates from all their patients (indeed, many say they would not), increasing the supply of doctors would force some reductions in price. As for the prediction that lower salaries would lead to a drop in quality, the rest of the world suggests that these concerns are unfounded. For as much as we spend on health care, our outcomes are the worst among high-income countries, almost all of which have found ways to produce healthier citizens at a lower cost.

Iglesias offers one place in our health care system where doctors do not appear to be mailing outsized invoices: Medicare. The federal government, as an enormous purchaser of services, has managed to bargain prices down to a more reasonable level than most insurance companies have. And while we often assume that doctors would not accept these lower rates from all their patients (indeed, many say they would not), increasing the supply of doctors would force some reductions in price. As for the prediction that lower salaries would lead to a drop in quality, the rest of the world suggests that these concerns are unfounded. For as much as we spend on health care, our outcomes are the worst among high-income countries, almost all of which have found ways to produce healthier citizens at a lower cost.

Resources:

How much do doctors really make? by Zach Nayer (Stat, July 18, 2017)

America’s Overpaid Doctors by Matt Yglesias (Slate, February 25, 2013)

The ‘Yawning’ Chart Med Students Fear by Ankita Rao (Kaiser Health News, February 13, 2013)

Couldn’t We Have 200 Medical Schools Instead? by Mark J. Perry (July 15, 2008)

How did Health Care Get to Be Such a Mess? by Christy Ford Chapin (New York Times, June 19, 2017)

The Evil-Mongering of the American Medical Association by Shikha Dalmia (Forbes, August 26, 2009)

Health Care Costs and Quality: A Look at Value-Based Health Care (Common Ground, June 15, 2017)